It’s hard to imagine Sydney having an epidemic of bubonic plague, but that’s what happened in 1900. The infection arrived on a visiting ship in January, and spread in overcrowded, unsanitary slums.

THE PLAGUE – PARRAMATTA’S PRECAUTIONS

I hadn’t realized there was a vaccine against plague, but a serum was used early on for those who would be highly exposed, such as doctors. and workers on the wharves. The Government had cabled the Pasteur Institute in Paris for extra supplies.

Both Dr Kearney and Dr Bowman of Parramatta were inoculated on Thursday. Speaking to a Parramatta medical man one day this week, an Argus reporter learned that scientists look with apprehension on paper money, as they realise that disease germs are in all probability carried from one person to another, extensively, by means of dirty notes. A suggestion is that all notes should be sterilised. (Argus March 29 1900)

The medical man referred to was Dr. James Kearney. He pressed for general hand hygiene. Sounds familiar doesn’t it?

There is a whiff of disinfectant all over Parramatta now. Gutters, drains, and dirty places have been disinfected by chloride of lime, phenol, and other strong smelling chemicals which have been provided to the council free of expense by the Government. It will take a lot of disinfectant to make sweet the sewer which the Government has made of the Parramatta River. (The Argus, March 29 1900)

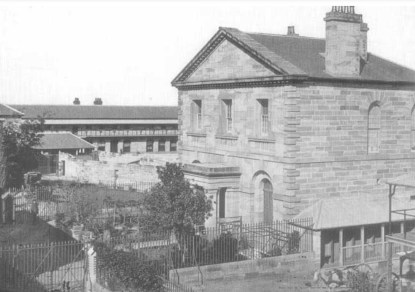

Mention of the river is interesting. Its pollution was another issue high on Dr Kearney’s agenda. Drains from the gaol and the mental asylum flowed into the river and he knew it was causing disease.

During my research for this piece I was intrigued by the parallels with our current pandemic. An article in The Argus a few weeks later stated that many people went about declaring they did not believe the disease in Sydney really was the plague.

Inevitably a case turned up just two miles away at Westmead, close enough to terrify the residents of Parramatta. On Saturday, April 7, Dr Kearney was called to see 33 year old James Mason. The man lived in a cottage at No 2 Good Street, which formed part of an orchard run by a Mr Beavis. Mason travelled into Sydney daily to sell fruit at the Darling Harbour markets. Mr Mason returned home on Friday evening feeling ill and feverish. As a precaution the doctor ordered the house to be disinfected. When he called again on Sunday he concluded the man had plague. He immediately reported the case to the Board of Health and contacted a fellow doctor, who confirmed the diagnosis;

The police were communicated with, and the house was at once isolated. There are six contacts – Mason’s wife and five children…The case is a typical one, with the bubonic swelling in the left groin. His pulse is good and he is keeping up wonderfully well, though his temperature is 104 degrees. (SMH, April 10 1900)

The more things change, the more they remain the same;

Here is the offending headline in the Daily Telegraph, which appeared on April 9;

MANY WAYS TO KILL A RAT

By now attention had shifted to the link between bubonic plague and rats. However, methods of extermination created more division. Some ignored the advice from authorities to poison rats even though the poison was issued free. They contended that the epidemic would more effectively be wiped out by paying small boys to kill them at the rate of 2p per head. This was branded as crazy;

Surely such an idea is the height of madness…The youngsters would of course handle their slain victims, carry them in pockets, or otherwise, pelt each other with them and thus scatter the infection broadly about. Is it likely that boyish rat catchers could be expected to observe due precautions as to pouring boiling water over the defunct rodents and only removing them with tongs? Boys are not built that way…’ (Argus, April 28 1900)

James Mason and his family were sent to the Sydney Quarantine Station, with the infected James transported separately. He remained there, slowly recovering, after his wife and children were judged safe and released. Dr Kearney strongly advocated for the family’s cottage to be burnt and compensation paid, but this did not take place. On May 12 The Argus reported that Mrs Mason would be allowed to move back in. It was a risk, especially as the cottage had been in a poor state of repair.

Nevertheless, thanks to Dr Kearney’s prompt action and wise advice to the community the Westmead case remained the nearest Parramatta came to having the plague in its midst.

FOR MORE ON THE SIMILARITIES BETWEEN THE PLAGUE AND OUR CURRENT PANDEMIC, CLICK HERE.

Thank you for so many interesting articles, I look forward to each new post!

Well thank you for taking the trouble to leave a message Christine. I love social history.